Haydn's symphonies and their nicknames

18 Dec 2023

News Story

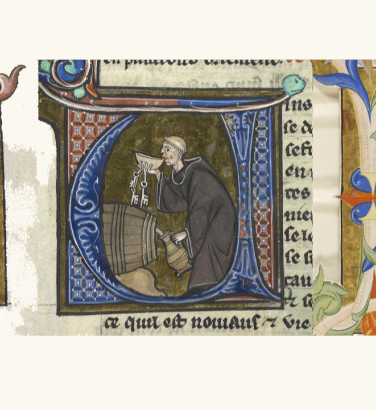

Can you identify four Haydn symphonies from these images? Answers at the bottom of this page ...

With over one hundred symphonies to his name, it is hardly surprising that several of Haydn’s should be better known by a nickname, more colourful and memorable that the more prosaic Symphony No n.

About three dozen of his symphonies have gained nicknames over the years, but only one of them was given by the composer himself. This is No 64 (performed by the Orchestra with Thomas Adès in April 2024), whose title Tempora mutantur comes from a Latin adage; loosely translated – and with apologies to Bob Dylan – it means “the times they are a-changin’”. Very few of the rest even date from Haydn’s lifetime, the trilogy known as Le matin (Morning), Le midi (Noon) and Le soir (Evening), Nos 6-8, being a notable exception. In truth, only the first of this set – which opens with a depiction of sunrise – is really warranted. The others’ connection to their respective times of day is a bit more tenuous, but that's nothing compared to the Mercury (No 43) and L’impériale (Imperial, No 53), the reason for their nicknames being lost in the mists of time.

That said, even the nicknames with a known story behind them can be questionable. Perhaps the most egregious is No 69 being called Laudon (after a popular Austrian field marshal) by Haydn's publisher, seemingly only to boost sales. Of the other symphonies named after specific people, only La Reine (No 85) truly deserves its appellation, having been a personal favourite of Marie Antoinette’s. Maria Theresa (No 48) may be attached to the wrong symphony altogether, as it was probably No 50 which was written in honour of the Austrian Empress. The same is true of the Miracle, so called because no-one was injured when a chandelier fell at its premiere: long thought to be No 96, research has shown this incident more likely took place at the first performance of No 102 - not that the nickname has been reassigned since.

We should also beware of Haydn symphonies named after cities. No 92 is known as the Oxford – where he conducted it on receiving an honorary doctorate from the University – despite having actually been written and performed in Paris two years prior to this. (It may come as some relief that Nos 82-72, collectively known as the Paris symphonies, were composed for that city and can be considered aptly named.) When it comes to the designation of his final symphony, No 104, as the London, however, this seems frankly arbitrary. The title applies to Haydn’s last twelve symphonies, Nos 93-104, as a whole, and there is nothing to connect the last of them specifically to the city.

The surprise might not be unaptly likened to the situation of a beautiful Shepherdess who, lulled to slumber by the murmer of a distant Waterfall, starts alarmed by the unexpected firing of a fowling-piece.

The story behind the naming of No 44, Trauer (or Mourning) goes further still, as it is now thought to be apocryphal. Legend has it that Haydn requested its slow movement be played at his funeral; if true, it seems a little strange this was only done at a memorial service some months later in Berlin. With music appropriate for such an occasion and a plausible story to go with it, however, the name has understandably stuck.

In most cases, however, it is their musical content which gave rise to the symphonies’ nicknames, ranging from specific associations to sometimes fanciful interpretation. If there’s a degree of imagination required to see how the Philosopher (No 22) and Schoolmaster (No 55) may represent these two professions, the pair of symphonies named for the music given to the horns is another matter. Hunting calls in the last movement of No 73 led to its recognition as La chasse (Hunt), while there’s no mistaking No 31 (Horn Signal) from the prominence of its fanfares. The Surprise at the heart of No 94 (performed by the Orchestra at our 50th Anniversary concerts in January 2024) is signposted by its nickname, but the sudden fortissimo chord in its slow movement is still apt to catch the unwary off-guard. (Unusually, this nickname is not universal: to German speakers, it’s the Paukenschlag or Drum Stroke – not to be confused with No 103, the Drumroll, named for its very quiet opening on the timpani.)

Specific orchestral effects lie behind the names given to Nos 38 (Echo) and 100 (Military), the latter bolstering its martial rhythms with a barrage of percussion. On the quieter side is the very end of the Farewell (No 45), when the only members of the orchestra left on stage are a pair of violinists – the other players’ gradual departure being Haydn’s positively avant-garde way of letting their employer Prince Esterházy know that his musicians were tiring of a prolonged holiday and wished to return home to their families. He took the hint, and they all left the very next day.

The first page of Symphony No 82 (Bear), in Haydn's handwriting.

Some of more imaginative nicknames also require a degree of explanation. Literary roots account for three of these – Feuer (Fire), Il distratto (The Absent-Minded Gentleman) and La Roxelane, Symphonies Nos 59, 60 and 63 respectively – the music of which is chiefly drawn from incidental music Haydn had written for plays of the same name. This may also have applied to No 49, which seems to have been originally connected to a play called The Quakers but would later come to be known as La passione (The Passion) thanks to a performance during Holy Week. In that respect, it makes a companion piece of sorts to Nos 26, 30 and 84, whose nicknames (Lamentation, Alleluia and In nomine Domine respectively) all came about thanks to a variety of religious connections.

Specific passages in the music account for a good deal of the remainder. The best-known of these is probably the Clock (No 101), thanks to the tick-tock accompaniment to the slow movement’s opening theme. Two others take their names from the natural world: the Hen includes a clucking figure in its first movement, while the finale of No 82 opens with a bagpipe-like drone then reminiscent of dancing ursines, hence its nickname of the Bear.

If this association with a form of entertainment we no longer condone today has not robbed the symphony of its name, there are others which have never really stuck. There’s a good reason for No 47 being called the Palindrome: the Minuet and Trio (which make up its third movement) both sound the same whether played backwards or forwards. It’s debatable whether an established nickname would help the symphony stand out from the crowd, but perhaps this increases the pleasure of introducing someone to an underrated work.

Either way, it is considerably easier to differentiate between such an enormous number of symphonies by using these nicknames. The story behind some of them may be a little dubious, but more than two centuries later, they have become an indelible part of musical history.

Clockwise from centre: Haydn himself, a digital Clock (Symphony No 101 in D), an ancient Roman Palindrome (No 47 in G), Carnaby Street in London (No 104 in D) and a Philosopher (No 22 in E flat), in this case Friedrich Nietzsche.

Related Stories

![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!![]()

The medieval carol

24 November 2025

For this year's Christmas article, we look back at some very early festive carols ...