Pulcinella and the dangers of (mis)attribution

16 Sep 2024

News Story

From left to right: Stravinsky, the commedia dell'arte character Pulcinella and Pergolesi

We have looked previously at the distinctions between the words arrangement, orchestration and transcription in concert listings, and today we turn our attention to another term sometimes seen in concert programmes, the more tricky 'attributed to'.

There is a good deal of ambiguity associated with attribution as it applies to music. It can actually be easier if we genuinely don’t know who wrote a given piece, as it can be safely ascribed to the mythical Anonymous (sometimes proclaimed as the most prolific composer of any age). Typically, this holds true of much older music, owing to the scarcity of surviving documentation giving any hints as to its composer, though there are some exceptions. The piano piece known in the UK as Chopsticks, for instance, follows the rhythm of the polka so cannot date from any earlier than the 19th century, but as for who wrote it, we simply don’t know.

There is a subset within this wide body of anonymous work which is specific to folk music, generally indicated by the word traditional. In some people’s eyes, this distinction actually adds a cachet of authenticity to this type of music, but this is probably best taken with a pinch of salt: the same people would have you believe that some composers (probably including the one to whom we owe Chopsticks) are so embarrassed by their music that they would rather not admit to it!

Attribution, on the other hand, is a decidedly grey area. The word can denote anything from “this is only an educated guess, which future research could well prove to be incorrect” to “we’re almost sure this is right, but it’s best to allow for a margin of error, just in case” – which covers an impressively wide gamut of certainty by the musical establishment.

Perhaps the most infamous case of misattribution is the Trumpet Voluntary once believed to have been written by Purcell, now recognised as the work of Jeremiah Clarke (and more properly called The Prince of Denmark’s March). The mistake appears to have originated in the publication of a transcription for organ in the 1870s, compounded by the music's increasing popularity in later arrangements by Henry Wood, which he put on frequently at the Promenade concerts (now the BBC Proms) he conducted for the best part of half a century. Clarke remains a little-known composer, and it has to be said that The Prince of Denmark’s March has benefitted considerably from its attribution to Purcell. Being associated with one of Britain’s greatest composers, however incorrectly, has granted the music stature it might otherwise not have gained, not least as a standard at wedding services.

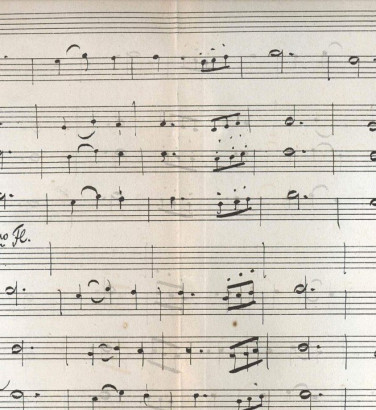

Stravinsky’s 1920 ballet Pulcinella is a different case again. A commission by the great impresario Sergei Diaghilev for his ballet company Les Ballets Russes, the score was to be based on music by Pergolesi, the Italian Baroque composer probably most familiar to us for his Stabat Mater. Stravinsky would later be rather evasive when it came to identifying which pieces of Pergolesi’s he had used:

Numerous fragments and unfinished or briefly sketched works which, fortunately, had evaded academic arrangers

(For ‘fortunately’, you may wish to read 'rather conveniently'.)

A 1979 recording of the ballet by Claudio Abbado helpfully lists what was then held to be the true composers of the original pieces: just under half were written by Pergolesi, most of the others being by one Domenico Gallo. (There were also two attributed to the ever-dependable Anonymous.) Further research has revealed that some of the music was actually composed by Carlo Ignazio Monza and Alessandro Parisotti, along with the decidedly un-Italian Unico Wilhelm van Wassenaer (a Dutch diplomat). We might think that Stravinsky and Diaghilev can't have been very scrupulous in describing Pulcinella as being based on Pergolesi alone, but it's worth emphasising that the latter was decidedly obscure at the time, and the other three remain so to this day.

As such, attribution is perhaps best defined as a best guess until conclusive proof comes to light. When it comes down to it, it doesn't really matter who wrote the music from which Stravinsky created Pulcinella. It's one of his freshest scores and, as a reinterpretation of (mostly) Italian Baroque music through a modern lens, it is undeniably fun, regardless of whose works lie behind it.

Related Stories

![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!