Not just Eurovision: an introduction to Swedish music

7 Oct 2024

News Story

Three Swedish composers: from left to right, Franz Berwald, Carl Michael Bellman and Kurt Atterberg

Imagine a music quiz in which you are asked to name one composer for every country in the world. When it comes to Scandinavia, Grieg probably comes to mind fairly quickly for Norway, as does Sibelius for Finland. Denmark might be a little more difficult until you remember Nielsen, but what about Sweden? When it comes down to it, many of us, asked about Swedish music, would immediately think of ABBA.

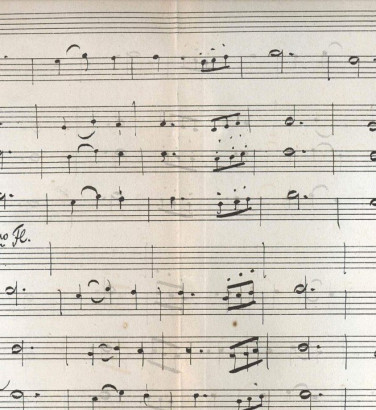

Historically, the country’s first significant composer is generally held to be Johan Helmich Roman, who is in fact sometimes called the father of Swedish music. Born into a family employed as royal court musicians, he spent six years studying in London in his early 20s, notably with Handel, whose music influenced him ever afterwards. This can clearly be heard in his best-known work – the suite of 24 movements now known as the Drottningholm Music put together for the wedding of the Crown Prince in 1744 – but he is also known to have written a wealth of choral music (including some 80 psalm settings) and instrumental music from violin sonatas to symphonies. Roman was clearly held in high regard for some decades after his death in 1758: his music is found in manuscripts dated as late as 1810.

In the second half of the 18th century, we find another court musician in Carl Michael Bellman, a rather Hogarthian figure who found inspiration in less exalted circles. He became especially known as the composer of songs about drinking and prostitution, both text and music being written in an incongruously elegant rococo style. This unexpected juxtaposition makes him something of a unique figure, one still difficult to classify, but he was as appreciated for this in his own lifetime as he is today: his patrons included King Gustav III, for whom Bellman was “the master improviser”. The German-born Joseph Martin Kraus, another court musician, was by comparison more conventional, but even he has become recognised for the strikingly dramatic nature of his compositions.

Franz Berwald’s reputation is generally thought to have improved posthumously, but it is more a case of his having been better appreciated outside his native Sweden during his lifetime. He met with greater success in Austria and Germany, but even then, he supported his musical career with work as an orthopedist in Berlin. His fortunes remained rather mixed when he returned to Sweden in 1849, after an absence of over 20 years: although he was named Professor of Composition at the Stockholm Conservatory in his final years, the Conservatory went back on its decision and the Swedish royal family had to intervene before his appointment was finally confirmed.

The early 20th century saw the rise of a number of important composers in the country. Wilhelm Stenhammer was especially influenced by late German Romanticism, while Hugo Alfvén is perhaps the most significant in the way his music portrays his native country, for instance in Midsommarvaka, or Midsummer Vigil (better known by its subtitle of Swedish Rhapsody No 1). Kurt Atterberg was another musician with a parallel career (in his case, as an engineer) but was a notably prolific composer. One of his most public successes came with the sixth of his nine symphonies, the winning entry in a 1928 worldwide competition to compose a work inspired by Schubert’s Symphony No 8, Unfinished. Stylistically, he was more conservative than his near contemporaries Hilding Rosenberg and Ture Rangström, in whose works we see a modernist strain enter Swedish music.

If later composers are less familiar to us, that may be because of the enormous impact of Swedish singers in the classical world. From Jussi Björling to Birgit Nilsson and Anne Sofie von Otter, they have made their mark across music of all periods, with Miah Persson among those who continue to fly the flag today. This is before considering Sweden’s ongoing importance in the world of pop music: countless hits of the last quarter-century – including songs performed by Bon Jovi, the Backstreet Boys and Taylor Swift – were co-written by one Max Martin, a Swedish record producer and songwriter. (We are assured he is no relation to our Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín.)

It is therefore high time we reacquainted ourselves with the remarkable music of Swedish composers, and several of our concerts this autumn give exactly that opportunity. You can hear works by Anders Hillborg and Madeleine Isaksson in Borealis (31 October – 1 November), while Andrea Tarrodi’s music can be heard both alongside Grieg’s Piano Concerto and Sibelius’ Symphony No 5 (7 – 9 November) and as part of our Digital Season (from 10 November).

Related Stories

![]()

Making a splash: water music beyond Handel

5 January 2026

We take a look at musical depictions of water, from trickling burns to the wide expanse of the ocean, to see what lurks below the surface.![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?