The double bass concerto

17 Feb 2025

News Story

Jamie Kenny, SCO Sub-Principal Double Bass (photo credit: Christopher Bowen)

This article is part of a series focusing on the concerto as written for specific instruments in the orchestra. With contributions from SCO players, we hope these give you some new insight into works you know and an idea of others they would recommend seeking out.

Of all the members of the string family, it is perhaps only to be expected that the double bass should have struggled to make much of an impact as a solo instrument. As the lowest-pitched of the strings, it was effectively the foundation stone on which the rest of the orchestra was built – think of the number of times the double basses are positioned centrally at the back of the stage, by conductors including Maxim Emelyanychev, and how this anchors the sound. Other instruments could step into a solo role, but put one of these imposing instruments out in front of the orchestra and that balance could be upset.

Considering how much of a gentle giant the bass is when heard on its own, easily overwhelmed by the rest of the rest of the orchestra, its status as a supporting player becomes clear. As a result, it takes a bit of effort and imagination on the part of any given composer to make something more of a double bass part, whether in the orchestra, a smaller ensemble or as featured soloist. Our Sub-Principal Double Bass, Jamie Kenny, was unfortunately not able to make any direct contributions to this article, but has given us plenty of useful pointers, including towards some of the lesser-known bass repertoire.

Not that there is anything to speak of in the Baroque era, despite a handful of works with a solo spot for the instrument. Telemann actually deploys a pair of them to great effect in his Grillen-Symphonie, a piece with a neobaroque counterpart in the trombone/double bass in Stravinsky’s 1920 ballet Pulcinella. The lack of any lyrical passages for the instrument, however, speaks volumes: if thrust into the limelight, its gruff sound typically ensured this was to comic effect.

The turning-point came in 1773, when the French composer Michel Corrette, author of a number of handbooks on playing various instruments, turned his attention to the double bass and proposed a new tuning for its strings: instead of being tuned in thirds – what is known as Viennese tuning – he suggested widening the interval. (It is now standard for it to be tuned in fourths, incidentally matching that of the modern bass guitar.)

A few double bass concertos which remain among the instrument’s standard solo repertoire do predate this innovation, however: Dittersdorf wrote two, in addition to a double concerto in which he paired the bass with the viola (another maligned string instrument), and there are a further two by Vanhal, who may well have been his pupil. These stand in stark contrast to those by Sperger: despite his having composed no fewer than 18 double bass concertos, none of those are held in the same regard.

Corrette’s manual had covered the 3, 4 and 5-stringed double bass, and this lack of standardisation in the design of the instrument persisted long into the 19th century. If anything, three strings was the preferred number, including by Domenico Dragonetti, the first significant double bass virtuoso. A Venetian by birth, he settled in London in 1794 and remained there until his death at the age of 83, but arguably his greatest contribution to music was showing Beethoven the true potential of the instrument while visiting Vienna in 1799.

Dragonetti’s performance of the latter’s Cello Sonata Op 5 No 2, with the composer at the piano, is supposed to have culminated in Beethoven embracing both player and instrument in his excitement. As Alexander Wheelock Thayer put it in his much-admired 1867 biography of the composer, “this new revelation of the powers and possibilities of [the double bass] to Beethoven was not forgotten.” This can be seen in the increasing prevalence of separate parts for cello and double bass in orchestral scores, instead of having them double up on the bass line as a matter of course – though listening to Bach and Mozart, for instance, it is clear that there were already worthwhile orchestral double bass parts long before this. (In Bach's Orchestral Suite No 2, however, the audience's attention is so focused on the solo flute that the demanding bass part can go unnoticed.)

Happiness is not a riddle

When I'm listening to that

Big bass fiddle

Besides conflicting ideas on the number of strings on the bass, there was also disparity regarding how best to hold the bow. Dragonetti preferred to hold it with the palm of his facing upwards, whereas Bottesini (sometimes described as the Paganini of the double bass) favoured the so-called French style, very similar to that used by cellists. The latter enjoyed a parallel career as an opera conductor – giving the premiere of Verdi’s Aida in 1871, for instance – and, at a time when instrumental performances were the norm between acts, was known for performing his own virtuosic fantasias on operatic themes on the double bass. As a composer, he was heavily influenced by the bel canto style of Italian opera, so his works (including another pair of concertos) introduce a lyrical dimension to the double bass sound, one arguably unmatched since.

Another important volume in the history of double bass playing, Simandl’s New Method for String Bass, was published in 1881, going into extensive detail about the role of every finger and thumb in playing in the instrument. This would not be superseded for the best part of a century, by François Rabbath’s New Double Bass Technique in 1977, written by a player whose ease with different styles – anything from transcriptions of Bach’s Cello Suites to music hall, accompanying (among many others) Charles Aznavour or Simon and Garfunkel – really show how far the instrument’s reach has since extended beyond the purely classical.

Saint-Saëns had, in the meantime, written what must surely be the double bass’ most famous solo piece, depicting an elephant (that can be either ungainly or remarkably elegant, depending on interpretation) among the menagerie of his Carnival of the Animals. It's part of the instrument's rich chamber repertoire, which ranges from Beethoven and Schubert to the present day, with Prokofiev's Quintet ranking among the more unusual with its scoring for oboe, clarinet, violin and viola alongside the bass.

There would be more substantial contributions to the instrument’s solo repertoire from Tubin and Françaix (polar opposites in style) and Koussevitsky, whose career as a double bassist has been all but eclipsed by his commissioning work – not entirely surprisingly, considering this includes a wealth of classics of 20th century orchestral music, from Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition to Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra.

Koussevitsky did, however, play a vital role in continuing to build on the double bass’ continuing popularity as a solo instrument, as evidenced by the plethora of concertos written since the middle of last century. Take your pick from Tan Dun’s Wolf Totem, the Divertimento Concertante by Nino Rota (better known as a composer of film scores, including the first two parts of the Godfather trilogy), Rautavaara’s Angel of Dusk, Maxwell Davies’ Strathclyde Concerto No 7 (an SCO commission) or Anthony Ritchie’s Whalesong and still you’re barely scratching the surface.

Peter Eötvös’ Aurora, a co-commission by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra which features in Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony (20-21 March, in Edinburgh and Glasgow), promises to shed light on yet another side of the double bass, in the composer’s words “sounding as powerful and colourful as the aurora borealis itself”. In the hands of former SCO Principal Double Bass Nikita Naumov, you can be sure of a revelatory experience.

Beethoven's 'Pastoral' Symphony

Mark Wigglesworth conducts Beethoven's hymn of wonder to the natural world, with former SCO Principal Nikita Naumov as soloist in Eötvös’ Aurora.

Related Stories

![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!![]()

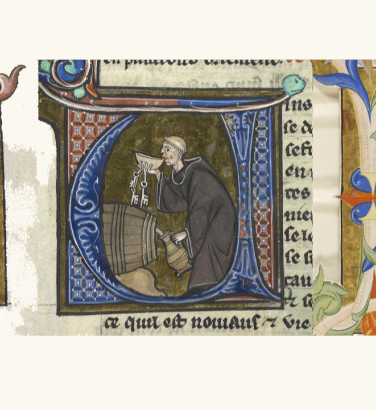

The medieval carol

24 November 2025

For this year's Christmas article, we look back at some very early festive carols ...